HUMANS AND

ANIMALS

More and

more people in Western societies see breeding of animals only as a previous

stage to a big massacre. Relationship between rearing and feeding is not done

any more, but between rearing and death of the animal.

By

extension, meat consumption is criminalized, and the consumer feels guilty.

The breeder

is seen as a monster who is suspected of having fun driving his animals to the

slaughterhouse.

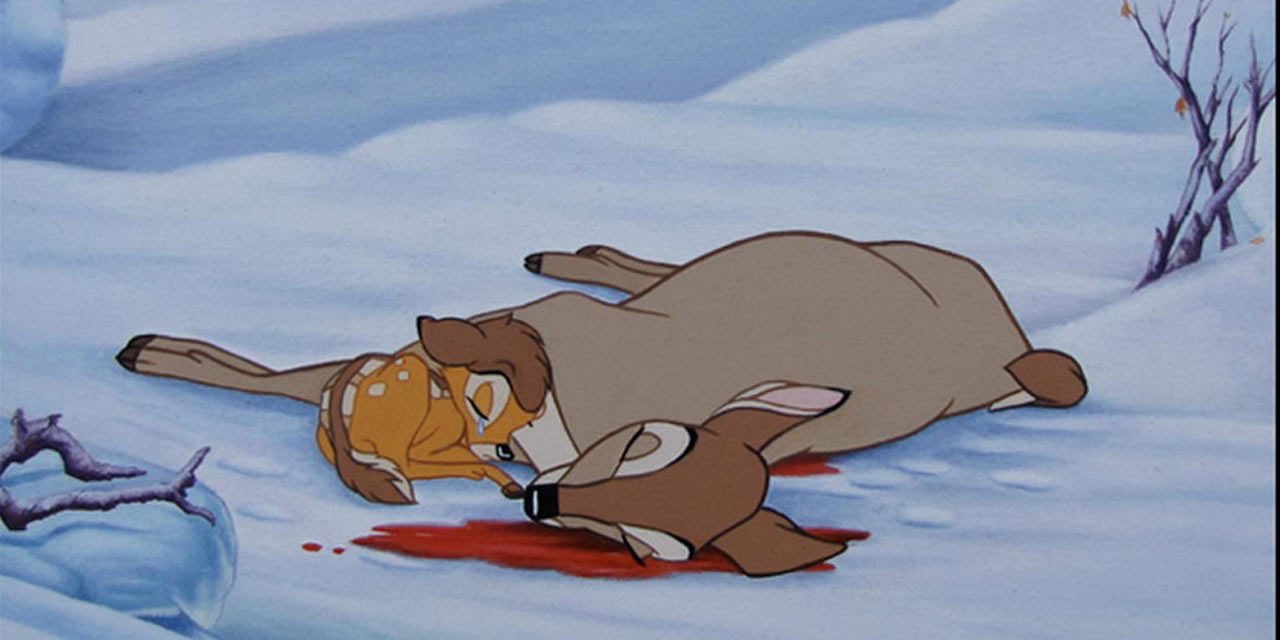

It's

sort of a drift of the Disney generation, which suffers deeply from what I call

the Bambi syndrome.

We feel

sorry and we cry over the fate of animals that die, whether it is the fault of

humans, or not.

It seems

very healthy to me, to wonder about our superpredator practices and our

excesses of consumers and of rich countries. It is becoming increasingly clear

that the richest societies consume too much meat, creating a potentially very

problematic ecological imbalance. Through our ancestral culture, consuming meat

is a symbol of wealth, so much so that when a poor society reaches a decent

standard of living, its first reflex is to eat meat frequently. In the same

way, in a poor society, the consumption of meat is reserved for celebrations or

to honor a guest.

But it seems

to me also very abusive (and even totally decadent) to put on the same plane

rhinoceros hunting, the breeding of chickens in battery, bullfighting, the

moderate consumption of meat, the production of honey, the use of draft horses

in biodynamics or the slaughter of baby seals.

The

human being is physiologically omnivorous and the consumption of meat provides

him with a number of essential nutrients that can't be found in plants. All

attempts to substitute these elements by non-vegetable sources have been

failures, and even dietary supplements based on synthetic nutrients don't have

the same level of assimilation.

But

this is where we are. Veganism is receiving ever greater reception and its

abuses, close to terrorism, are viewed with a certain benevolence by

governments of all sides. Our politicians have become pure bureaucrats, much

more attentive to opinion polls than to scientific results, and to the actual

results of the decisions they make (we communicate a lot about the decisions

made, we explain at length what we expect, and collateral catastrophes they

provoke are left to the following ones).

Science

becomes embarrassing when it does not go in the direction of politically

correct thinking. This is the case for meat consumption, as for neonicotinoids,

glyphosate or GMOs.

We are in

the midst of media, social and political decadence. Populism has the power, but

not the usual, the vociferous, the one we see coming. This one is devious and

discreet, no inflammatory speeches, no obvious scapegoats. Everything is in the

manipulation of information, speech is first given to antiscience, to fear.

This is the

end of the scientific empire.

This

decadence and rejection of science is very evident in most European governments

and in the United States government, for example.

In

early June, the French newspaper L'Express published an article that challenged

me about the new French law on agriculture and food, in the form of an

interview. I don't repeat the first question that concerns the law itself, and

only interested the French. Those who want to read this part can click on the

direct link to the original article.

However,

most of the article deals with the relationship of humans with animals, and

seems to me quite fundamental.

This is an

interview with Jocelyne Porcher, a breeder, sociologist and researcher, with a

peculiar personal and professional background.

Original

article:

"Food Law:" No progress

for animals "

By Michel Feltin-Palas, published

on June 02, 2018

"How does a Parisian secretary find

herself one day raising chickens, sheep and goats in the Toulouse region?

Initially, Jocelyne Porcher is a neo-rural like any other, one of these young

women eager to leave the capital, its stress and pollution, to get closer to

nature. She takes the leap in the 1980s. Here she is in a village in the South

West [of France], in contact with peasants respectful of their land. She is

happy.

In 1990, it's the shock. She has

just returned to agricultural studies and finds herself in an industrial pig

farm in Brittany. Another world: "I raised animals because I loved their

company, I was looking after their well-being, I was taking care of them, I was

thinking about them day and night, I had a real conversation with them. In Brittany,

they were perceived as mere objects, resources intended to produce animal

matter, they were beaten, mutilated, insulted, with only one purpose: money.

"

From this double experience, she

draws a conviction: the traditional and capitalist breeding are two universes

that everything opposes, in their practices as in their values. And she refuses

that the first, where the man lives in symbiosis with his animals, be swept

away by the excesses of the second. She then goes into research, specializes in

the affective relations between men and animals, passes a thesis, is hired at

the National Institute of Agronomic Research (INRA), publishes books (1). A

path that allows her today to denounce both the excesses of agribusiness and

the ultras of the animal cause. Interview. "

[…]

"The government is putting

forward the doubling of penalties for the offense of animal abuse and the

animal welfare training in agricultural high schools. Is that not going in the

right direction?

Any piece of legislation obviously

includes some positive measures, but it's still a drop in an ocean of violence.

For my part, there is only one article that I really approve: it's the

authorization to experiment with mobile slaughter, an idea that I have been

defending for a long time with my association “When the slaughterhouse comes to

the farm”.

What would be the advantages of

such a solution?

Today, animals are pushed into a

truck that takes them to an unknown place to be massively killed by men they

have never seen. Slaughter on the farm avoids these drifts. This is a progress

for breeders, who can watch over their animals from birth to death; a progress

for the consumer who is guaranteed perfect traceability, and a progress for

livestock, which avoids all stress and suffering.

Any suffering, really?

Yes, as the animals are stunned and

unconscious at the moment they are bled. There is neither physical suffering

nor mental suffering.

Curiously, you are very critical of

the L 214 association [a french animalist association that militates for the

prohibition of any type of animal exploitation, and against the consumption of

meat], which also contributes to denouncing the slaughter conditions of

industrial slaughter.

We differ on the purpose of the

action. L 214 is abolitionist: it advocates for a farming without livestock and

a rupture of domestication links. For my part, I consider that domestication is

not only necessary for man, but that farm animals and those of company also

have an interest.

What do you mean?

It's very simple to understand: in

nature, many animals would have a very short life expectancy if they were not

defended by humans. A sheep or a goat isolated in a mountain automatically

becomes a prey! And the life of a mouflon in a territory where wolves roam is

dominated by anxiety. That is why in the Neolithic period, about 10 000 years

ago, domestication relations were created, with the agreement of the concerned

species. The man and the goat, the man and the cow, the man and the pig, formed

an alliance and understood that they had a mutual interest in living together,

through a system of gifts and counter-gifts.

Is not this a vision a little

idyllic? When the man takes the wool, the milk and the meat of a sheep, what

does it bring him in return?

Food and protection. But we must go

further. This relationship is not limited to issues of interest: it goes well

beyond. In reality, man has always needed the company of animals. It was true

at the time of the Neolithic and it has not changed. This is why today's

breeders are often urban young people who choose this job. And as many French

people own cats and dogs.

There is still a big difference

between farm animals and pets: you kill cows and pigs, not your cat or dog!

Why would they do it? They have no

reason to do so because they make a living differently. But put yourself in the

shoes of a shepherd who spends all his days caring for a herd of cows. He must

from time to time sell the milk or meat of his animals to earn income.

You present the situation as an

"alliance" between man and animals. But animals are forced to work

for us.

But work is not necessarily

alienation. It has long been known how central it is in human existence. I

showed with my team that it can be the same for animals too.

Really?

Observe a guide dog or a sheepdog:

don't you see how happy he is to work? The same goes for a horse or a cow: all

these animals invest themselves in the work that is asked of them, try to

understand the requirements of their master and, when they succeed, get a real

satisfaction.

The "antispecies", who

refute the superiority of man over animals, believe that our duty is to change

our diet and to free animals.

They are wrong! Go see the ewes who

live surrounded by wolves in the Alps and ask if they want to be

"liberated". Those who hold this speech often live in the city and

have an idealized and disconnected image of nature. In fact, they seek to free

themselves from the moral weight and guilt they feel in seeing the human race

raise and kill animals. It is better to try to understand what connects us to

animals, to improve their conditions of life and death, than to get rid of the

problem, especially as we would only create another, even more serious.

Which?

If humanity stops raising domestic

animals, we won't stop eating meat. So, we will go to meat in vitro, produced

from cells. While dogs and cats, which we are supposedly shamefully

appropriate, will have to be "released" and replaced by robots. Don't

be fooled - this is tantamount to a historic change in the anthropological

paradigm. After living with domestic animals for 10,000 years, man should break

with them to build a humanity based on artificial intelligence and food

biotechnology. It's undoubtedly exciting from an intellectual point of view,

but, from my point of view, it's a frightening prospect for our human becoming,

or rather inhuman. "

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire