NATUREL VS SYNTHÉTIQUE – DE LA PRODUCTION

DES PYRÉTHRINES NATURELLES

A la suite de mon précédent article de

cette série sur les pyréthrines et les pyréthroïdes (https://culturagriculture.blogspot.com.es/2017/04/101-naturel-vs-synthetique-3.html), j’ai reçu une question, le 5 avril, sur la version française « Bonjour,

pour produire des pyréthrines naturelles, il convient de cultiver des fleurs de

pyrèthres. De plus en plus de pyrèthres, puisqu'il y a de plus en plus d'agriculture

biologique. Savez-vous si la culture de ces fleurs de pyrèthres se fait en

agriculture biologique ? »

Ma réponse a été « Je n'ose même pas

penser que des champs de pyrèthre destinés à la fabrication de pesticides bio

puissent être cultivés avec des pesticides de synthèse. Mais, y a-t-il un

contrôle? Je n'en sais rien. »

Mais Wackes Seppi, connu des milieux

agricoles francophones pour son blog (http://seppi.over-blog.com/)

abondamment fourni et critique, me passe un lien en français (https://erwanseznec.wordpress.com/2016/10/12/comment-le-bio-externalise-les-pesticides-conventionnels-chez-les-pauvres-121016/), accompagné du commentaire « Vous allez tomber sur le

cul ! »

Et je suis tombé sur le cul !!!

Erwan Seznec est un journaliste indépendant

français, connu sur ses prises de position critiques, allant souvent à

l’encontre de la bien-pensance sociale et du politiquement correct.

Au mois d’octobre 2016, il publiait sur son

blog l’article suivant, que je reproduis en intégralité, comme d’habitude.

« Comment le bio externalise les pesticides

conventionnels chez les pauvres - 12/10/16

La

marée des articles annonçant la disparition des pesticides dans les jardins

particuliers à l’horizon 2019 a opportunément recouvert deux écueils

conceptuels un peu gênants. Le premier, développé dans l‘enquête sur les pesticides bio parue dans

Que Choisir, est que les pesticides bio, qui resteront autorisés, ne sont pas

tout à fait sans inconvénient. Par ailleurs, ces pesticides bios ne suppriment pas l’emploi de

phytosanitaires conventionnels. Dans le cas de la pyréthrine, ils

l’externalisent en Afrique de l’est et en Papouasie Nouvelle-Guinée.

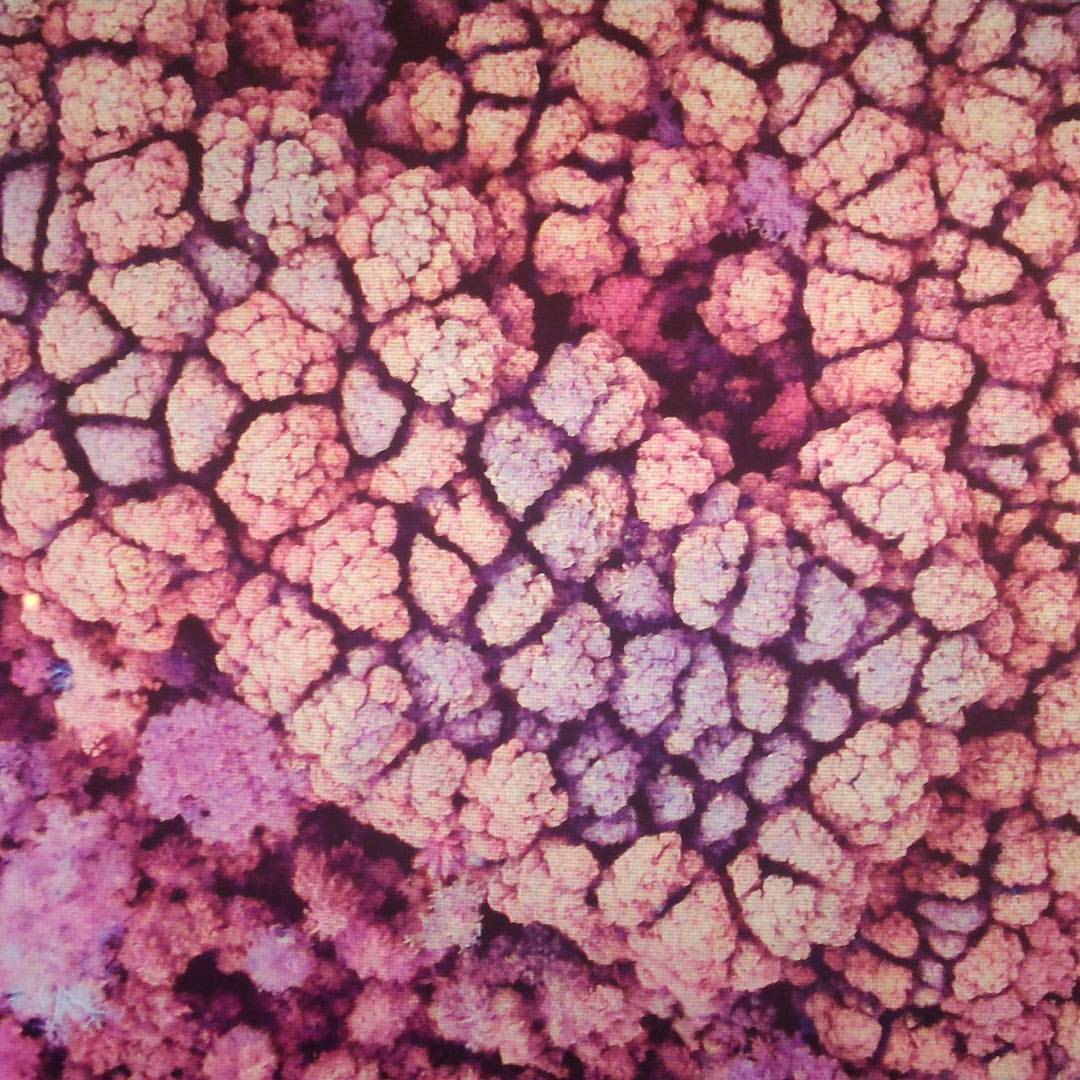

Les

pyréthrines sont des insecticides produits à partir de fleurs de pyrèthres de

Dalmatie et de chrysanthèmes. On les retrouve dans des dizaines de préparation

homologuées en agriculture biologique.

Les

fleurs en question, bien entendu, doivent être cultivées quelque part. En

l’occurrence, c’est en Tanzanie (60% de la production mondiale), en Papouasie

Nouvelle-Guinée et au Kenya. On apprend dans ce document kenyan qu’il faut

52.000 plants pour obtenir 25kg de poudre. Ici, on découvre que le pyrèthre,

sans surprise, est attaqué par des ravageurs et des champignons.

Et

dans cette étude australienne fort détaillée (1), le lecteur perspicace trouve

confirmation de ce que le bon sens lui suggérait peut-être déjà. Pour traiter

ces cultures non-alimentaires, les Tanzaniens et les Néo-Guinéens n’ont aucune

raison d’utiliser des pesticides bio, plus coûteux. Ils emploient l’arsenal

conventionnel.

«

Dans les cultures de pyrèthre en Afrique de l’est et en Papouasie Nouvelle

Guinée », écrivent les chercheurs australiens et américains, « les fongicides

efficaces contre l’ascochytose du chrysanthème (ray blight, ndlr) comprennent

l’éthylène-bis-dithiocarbamates, le captan, le bénomyl, le chlorothalonil et le

dichloronaphthoquinone ». Par ailleurs, « une panoplie d’autres produits

appartenant au groupe des inhibiteurs de la déméthylation, incluant le

difénoconazole, ont prouvé leur efficacité », à condition de procéder à «

plusieurs applications de ces fongicides ».

Le

difénoconazole est à peu près tout ce que proscrit l’agriculture bio : toxique

pour les mammifères, pour les milieux aquatiques, et persistant avec une

demi-vie de 1600 jours dans certaines conditions. C’est page 5 de l’étude (1).

Dans

les deux ans qui ont suivi les tests d’efficacité, se félicitent les

chercheurs, « 90% des producteurs de pyrèthres en Tanzanie » ont adopté le

programme fongicide. Les auteurs australiens sont de l’université de Tasmanie,

où le pyrèthre est également cultivé. On peut penser qu’ils ont de bonnes

informations sur l’Afrique. MGK, le leader australien du secteur, a des

exploitations en Tanzanie.

En

2010, des chercheurs allemands avaient relevé le paradoxe. Le Kenya produit des

fleurs séchées de pyrèthre, mais « 95% de la pyréthrine brute est exportée vers

des pays développés plus soucieux de l’environnement, où elle est vendue à prix

premium, laissant le Kenya importer des pesticides de synthèse meilleur marché

» (2).

Le

cas kenyan laisse penser que la culture du pyrèthre n’est pas une mince

affaire. De 70% du marché mondial au début des années 2000, sa production est

tombée à moins de 5% dix ans plus tard, pour cause d’irrégularités dans les

rendements. L’agriculture est un métier passionnant mais difficile.

Erwan

Seznec

PS

: les termes techniques ont été traduits à partir du site

http://www.btb.termiumplus.gc.ca. Je remercie par avance les lecteurs qui me

signaleraient des erreurs.

1)

Diseases of Pyrethrum in Tasmania: Challenges and Prospects for Management. http://apsjournals.apsnet.org/doi/pdf/10.1094/PDIS-92-9-1260

2)

« Incidentally, Kenya is the leading producer of a natural pesticide,

pyrethrin, which is a broad-spectrum insecticide made from dried flowers of

pyrethrum (Chrysanthemum cinerariaefolium). However, 95% of the crude pyrethrin

is exported to more environmentally conscious developed countries, where it

earns a premium price, leaving Kenya to import the cheaper toxic synthetic

pesticides ». Potential environmental

impacts of pesticides use in the vegetable sub-sector in Kenya. »

J’ajoute, car ça me parait important, que

le document australien explique aussi, en page 2, que pour une culture de

pyrèthre performante, l’usage des herbicides est nécessaire, ainsi que

l’irrigation intensive par aspersion accompagnée de l’utilisation de

fertilisants. On y apprend enfin que la récolte des fleurs est mécanique.

Tous ces critères sont a priori contraires

à la philosophie de l’agriculture biologique.

Ma surprise fut telle que je décidai de chercher

un peu plus. Et je suis tombé sur un document kenyan, de HighChem Agriculture,

une entreprise de conseil et d’accompagnement des producteurs de pyrèthre, qui

vend aussi les semences et les productions obtenues. Ce document explique les

grandes étapes de la culture (http://www.highchemagriculture.co.ke/en/pyrethrum-farming.php) et on y apprend que le contrôle des ravageurs se fait sur la base de 3

insecticides de synthèse, le carbaryl (un carbamate interdit en Europe depuis

2006), le dioxathion (un organophosphoré interdit en Europe depuis 2002) et, ô

surprise, l’alphacypermethrine, un pyrethroïde de synthèse.

Et tout ça pour produire une pyréthrine

naturelle, autorisée en agriculture biologique ?

Voilà, voilà.

Que doit-on en penser ?

Ce que je vous ai déjà dit à plusieurs

reprises : le bio est avant tout un

marché juteux, pour lequel tout est permis, en particulier de tromper

allègrement le consommateur, mais aussi l’agriculteur (qui, dans ce cas,

achète des pyréthrines naturelles en toute bonne foi, sans savoir qu’il se fait

rouler).

Ce marché est avant tout développé dans les

pays les plus riches (en particulier en Europe), dans lesquels il est de bon

ton, il est même du plus parfait bobo de consommer bio. C’est mieux pour la

planète !

Oui, sauf que, d’une part le bio a beaucoup

de côtés obscurs qui sont systématiquement passés sous silence, et d’autre part

faire du bio en Europe est beaucoup plus

facile si les aspects les plus négatifs sont délocalisés à l’autre bout de la

planète !

On est encore une fois dans le marketing,

dans la communication.

On passe sous silence tous les aspects

non-vendeurs, pour ne pas choquer le consommateur. C’est le même problème avec

les OGM. On n’en produit presque pas en Europe, mais on en importe par bateaux

entiers, produits dans d’autres parties du monde.

Là c’est pareil. Au contraire de ce que

croyais, candide et naïf, les pesticides bio ne sont pas produits selon les

critères incontournables de l’agriculture biologique.

C’est quand même un comble !!!

Ça ne retire rien au mérite des

agriculteurs qui produisent en bio, que ce soit par choix philosophique, ou

économique. Mais ils doivent le faire avec un nombre limité d’alternatives face

aux problèmes phytosanitaires qu’ils rencontreront de toute manière, et qui les

oblige à travailler de manière extrêmement précise car ils ont très peu de

marge d’erreur.

Mais ça démontre juste qu’au bout du

compte, l’agriculture biologique est une

vaste supercherie, qui sert à un certain nombre à s’engraisser sur le dos des

agriculteurs et des consommateurs.

Je vous l’ai déjà dit, je le répète une

fois de plus, et ce ne sera pas la dernière, l’avenir n’est pas à l’agriculture biologique, il est à la Production

Intégrée ou Production Raisonnée (https://culturagriculture.blogspot.com.es/2014/11/32-les-methodes-de-production-4-la.html), ou plus récemment Agroécologie.

Bref, l’usage des pesticides est

indispensable pour une agriculture durable, et une production d’aliments plus

juste et plus écologique.

.jpg)